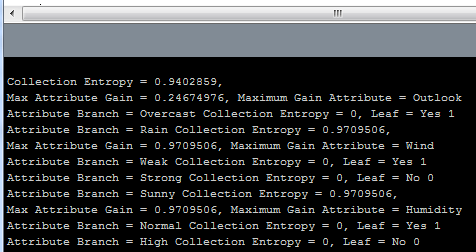

So the moment I’ve been working toward for the past few weeks has arrived. I’ve finally started the process of having my decision tree program in Processing output generated code that can be run on the Arduino platform. In this first day I’ve made a huge amount of progress, going from nothing to having all the necessary code generated to create a function which can be run on the Arduino. What I’ve done is allow the decision tree program in processing to create a .h header file with the name of the tree as the name of the generated function. The inputs to the function are integer variables whose names are the names of the attributes used to create the tree. The auto-generated code includes comments which tell the name of the function and the date and time it was generated. Once the .h file is generated, all I have to do is use the decision tree function with the Arduino is place the generated “tree_name”.h file in the Arduino libraries folder and then add #include <“tree_name”.h> to my Arduino sketch. From there on the decision tree function will simply take in integer inputs for the attributes and output the decision as an integer which is the output level. I’ll be working to clean up all my code and examples and to run some data sets through the system for verification and to determine percent accuracy. For now I’ll leave you with some of the auto-generated code and the decision tree diagram that goes with it.

/* tennis decision Tree file for Arduino */

/* Date: 13 Feb 2012 */

/* Time: 18:22:33 */

#ifndef tennis_H

#define tennis_H

#if defined(ARDUINO) && ARDUINO >= 100

#include "Arduino.h"

#else

#include "WProgram.h"

#endif

int tennis(int Outlook, int Temp, int Humidity, int Wind){

if(Outlook == 0){

return 1;

}

else if(Outlook == 1){

if(Wind == 0){

return 1;

}

else if(Wind == 1){

return 0;

}

}

else if(Outlook == 2){

if(Humidity == 0){

if(Temp == 0){

return 1;

}

else if(Temp == 1){

return 1;

}

else if(Temp == 2){

if(Wind == 0){

return 0;

}

else if(Wind == 1){

return 1;

}

}

}

else if(Humidity == 1){

return 0;

}

}

}

#endif